ritual and the return to craft

Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful. - William Morris

CRAFT, DESIGN + ART

“People have very odd associations with craft,” says Jonathan Anderson, creative director of Loewe, and the man who first conceived of the [Loewe Craft Prize] award. “We see it as a very nostalgic thing but, in the digital age, we want to reconnect with something… and no matter what age demographic or background you’re from, certain objects just have a resonance: they make you feel happy.”

In a 2017 article about his role at Loewe, the New York Times said “Anderson’s concepts resonate because he has managed to speak to our moment, to our inchoate and inarticulable yearning for the earthbound, the slow, the imperfect and the anthropological.” He came to that role, young but with a POV that has often been considered counterintuitive -- especially when he began to expand the design house to include the Loewe Craft Prize, which gives a grant to a family or artisan that is carrying on an arts and crafts tradition. Applications spill in from around the world, and in a multitude of disciplines from woodcarving, to ceramics to weaving.

In 2017, Anderson established the Loewe Craft Prize, which offers a sizable grant to one artisan per year in hopes of elevating the conversation around craft, but also in stewardship of techniques, traditions and regional aesthetics.

This recontextualizing of craft as luxury is an interesting topic that has spanned decades. Often differentiated from Art or Design, Craft is sometimes known as the Lesser Arts, and the criteria of beauty and usefulness remain key to the definition. There is a hierarchical nature to the valuation and in the “Craft in Conversation” series, Loewe invited Anatxu Zabalbeascoa, Deyan Sudjic, John Allen, and Gijs Bakkerto debate their respective thoughts.

Beautiful, Useful Things

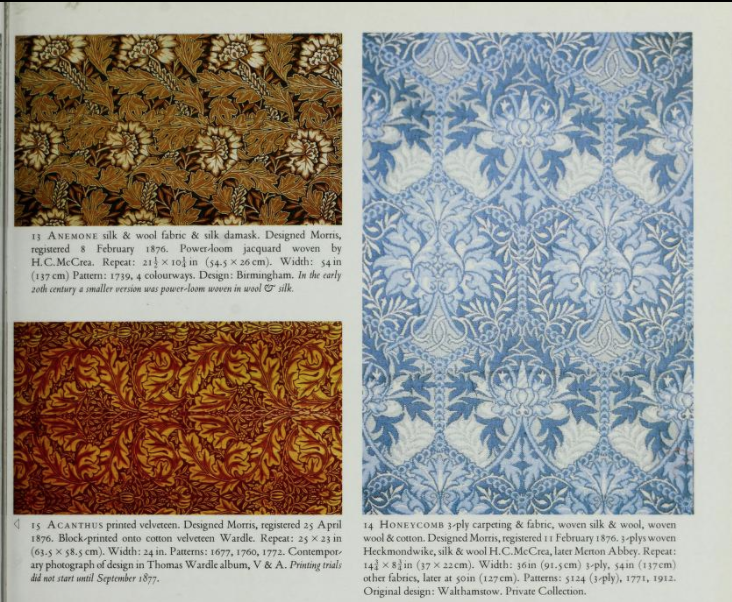

(top) A room decorated in the Arts and Crafts style by William Morris, with furniture by Philip Webb. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, photograph, John Webb (bottom) William Morris Textile designs

The Arts and Crafts movement was born out of the mind and works of William Morris in the 1860s, who believed people should be surrounded by beautiful, well-made things. We are at an inflection point where the perspective of Morris resonates. In W Magazine, Alix Browne notes:

(above) John Ruskin & William Morris Aesthetics documentary by Peter Fuller, (below) Yanagi Sōetsu

The genesis of the Arts & Crafts movement of the 1800s is rooted in a dialogue between John Ruskin and William Morris, which is expressed in depth in Peter Fuller’s documentary(left). While over an hour and a half long, advocates for craft’s meaning beyond a production mechanism — instead a connection point between material, humanity and beauty.

He also advocated that craftspeople “work as if this were the natural thing to do; they create as if this were the natural thing to do; they give birth to beauty as if this were the natural thing to do…This natural, unforced beauty is the result of a kind of unconscious grace. This grace is a special privilege of craftsmen and leads them to a realm of blessed unawareness. Without consciously thinking whether something is good or bad, creating as if it were the most natural thing in the world to do, making things that are plain and simple, but marvelous, this is the state of mind in which artisans do their finest work.”

“It [craft] must be something ordinary, born from the ordinary. There are cases where the plain and ordinary is more significant than the extraordinary.”

“The small things of life were often so much bigger than the great things. The trivial pleasure like cooking, one’s home, little poems, solitary walks, funny things seen and overheard” Barbara Pym

This is an excerpt of an article from our current issue. Subscribe to read more on:

Understand the intrinsic benefits of handmade objects and why they will always outlive the machine made

Explore ways you and your company can incorporate craft into your brand at any level

See how the internet, social media and certain shopping platforms are allowing for small makers around the world compete with the largest manufacturers of home goods and clothing

Learn why craft isn’t going anywhere for the foreseeable future