shapeshifting nature

Glass Flowers at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

TRICK OF THE EYE

Over the course of fifty years, from 1886 to 1936, Czech father and son glass artists, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, produced 4,300 glass models to represent 847 plant species for Harvard Professor George Lincoln Goodale, founder of the Botanical Museum. At the time, botanical models were made of paper mache or wax, crudely approximating petals, leaves and stems. The Blaschka glass flowers are life-size and remarkably anatomically accurate. They deceive the eye with such likeness to the material properties of plants. The Blaschka’s family glassworking business, an example of technical skill and craftsmanship passed down through generations, produced objects that intersect art and science, and allow for further understanding of the natural world.

The precise resemblance of Blaschka’s flowers renders the glass invisible. One has to be reminded of their actual medium. But, they are in fact, copies of nature. In his essay Copies and Facsimiles, Mats Dahlström states, “Let us recognize that the terms original and copy are mutually dependent. The everyday idea of an original supposes the existence of copies (or forgeries) of that original, and there would be no copies if there were no such original. So between original and copy there is always a supposed relationship, or perhaps movement.” Dahlström explains that in The Sophist, Plato discusses simulacra, works of art that strive for the effect of authenticity. Simulacra show up in two forms. First, there is the exact, proportionate reproduction of an original, like the Blaschka glass flowers. Second, there is a reproduction which has been intentionally manipulated during production. Work that exemplifies this category reveal the shift in medium from original to copy.

SIGNIFIER / SIGNIFIED

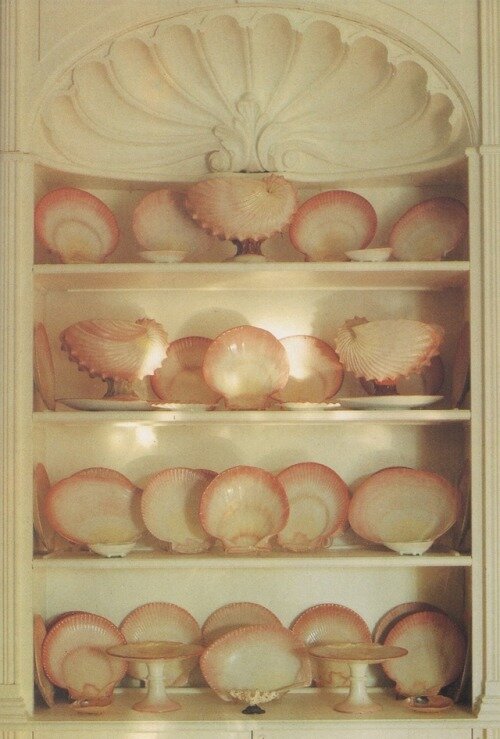

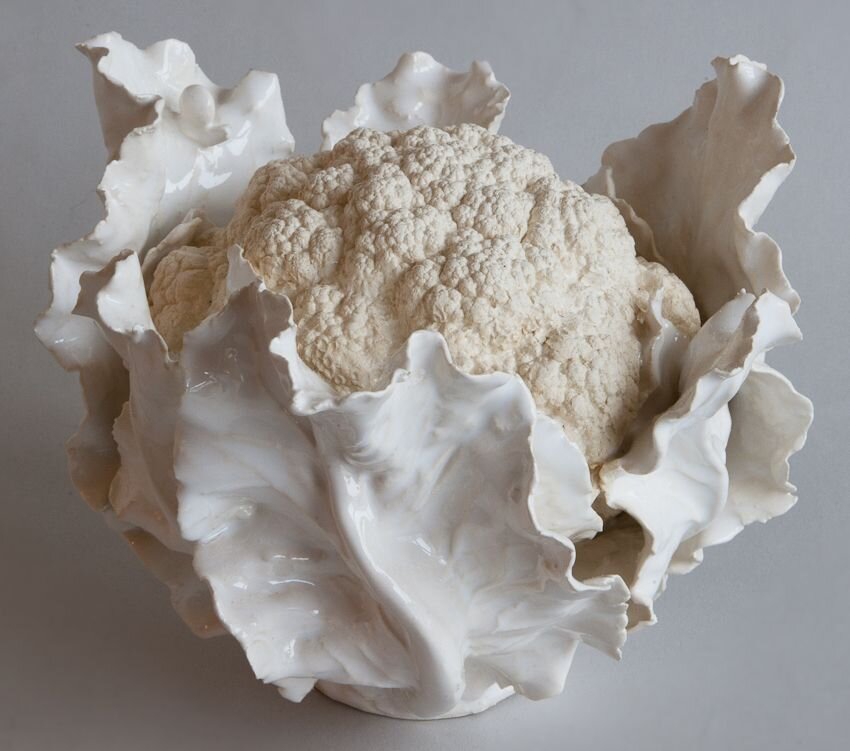

Wedgewood pottery pearlware, Jean-Paul Gourdon cauliflower soup tureen, Dodie Thayern lettuce ware

In an artists’ choice to replicate natural forms, there are a range of material properties to consider. Jean-Paul Gourdon chooses to render his work in white, whereas Dodie Thayern and Wedgewood take on original hues of the source inspiration. In all three examples, cauliflower, lettuce and shells are still recognizable. The nameable organism survives the material translation.

If we look at this body of work through a linguistic lens, the preservation of natural, nameable traits is essential to the works’ success. Studies of Structuralism and Poststructuralism in Linguistics are interested in the way meaning is communicated through signifying systems. We define and name our world by designating a sound and image to a concept. The word “tree” and visualization of leafy branches supported by a trunk are associated with a specific mental idea. Our society agrees upon this because it is ingrained in our brains at a very early age. However, the relationship between signifier and signified is arbitrary in Western culture. The letters forming the word “tree” do not resemble the concept. The signifier/signified relationship is not given by the world around us, but produced by the symbolizing system we learn.

This is an excerpt of an article from our current issue. Subscribe to read more on:

Understand why nature is again becoming the greatest source of inspiration for product development and the responsibilities that come with it.

Learn the value of creating something original to sustain long term success versus creating derivative products that only make originals worth more

See how nature and culture are and will forever be linked and how that affects design trends today